Lighten Up!

Dr. Terry M. Trier

Over the years my backpacking trips started to get longer and longer and my pack got heavier and heavier. Eventually I was forced to think seriously of ways to reduce the load. One thing that helped was when I jettisoned the tent and started using a tarp. That reduced my load by four or five pounds. When they began making ultralight tents, I started using them again but after a few years, I chucked the tent and went back to the tarp. For bugs, I wear a head net with wire hoops when I sleep. However with some of the new ultralight tents out now, I find myself once again rethinking my shelter options.

One of the problems I had to deal with was my penchant for nature study. This meant usually hauling several field guides into the backcountry. Photography was another. My 35 mm SLR camera and telephoto lens often accompanied me. Add some hefty binoculars for birding and you are talking about some serious weight for a two week trek. It usually took two or three days for the endorphins to kick in to kill the pain between my shoulder blades. In all honesty, though, it seemed like I was having fun. Really.

|

| The Victorinox Camper (2.7 oz) and Pioneer (3.0 oz) are sturdy enough to handle your toughest backpacking knife task. The saw blade is an excellent option for cutting stakes and poles. For backpacking well-marked trails, this small compass by Suunto may be all that is required and can save you an ounce or two. |

For the first 25 years of my backpacking experiences, I usually traveled with only one knife, a Swiss Army Victorinox Craftsman. I really donít recall needing any more knives than that during that time. However, about 13 years ago I was hiking with a friend who ripped his hip belt. Fortunately I had brought along a Leatherman tool, a three-cornered needle, and waxed nylon thread. By using the pliers on the Leatherman to grasp the needle and force it through the heavy webbing, I was quickly able to mend his pack and get us back on the trail. Ever since, Iíve never hiked without pliers of some sort and Iíve found them quite useful for repairing everything from broken wristwatch bands to sticky valves on cook stoves.

Hiking with 65-70 pounds on your back is truly a young manís game and since Iím now on the "dark side" of 50, I find myself more frequently scrutinizing every ounce I carry into the wilds. In many ways Iíve found this quite exciting because even though I donít have the endurance I once had, I can still cruise along the trail at an enjoyable pace and that annoying ache between the shoulder blades doesnít come around so often anymore. Iíve found that with 35 pounds on my back, I can travel easily and comfortably for a week, not to mention eat like a pig. The trick is to know what you donít need.

Sometimes itís pretty easy to identify rookie backpackers in the backcountry. They are often the ones with the large hatchet, huge knife, or maybe even a khukri. Big chopping tools designed to conquer the wilderness. And while this kind of cutlery is certainly fine for off-trail bushwhacking, it has little application along the well-worn trails found in most of our remaining wilderness areas in the lower 48 states. Modern backpackers carry their shelter and cookstove. High tech sleeping bags are warm enough to survive sub-zero temperatures. However, their synthetic shells quickly melt from sparks if used to sleep next to a fire. And if you are like many backpackers and sleep in a nylon tent, wear fleece, down jackets, or nylon shirts and pants, much of your gear is at risk from stray sparks. This means that fires in the backcountry are more a luxury than a necessity.

Even if you donít have a tool for heavy chopping, building and maintaining a fire is easy to do without such cutlery. The large chopping tools are best suited for "old style" camping, where woodcraft is an essential element of the backwoods experience. This is not the style of camping you will find along well groomed hiking trails. Activities like making bough beds, constructing rustic furniture, or building shelters from saplings are often banned in many wilderness areas and fires are frequently restricted to specific sites even in vast wilderness areas like the Boundary Waters of Minnesota. So the truth is that the big "survival knife" rookie backpackers like to carry into the backcountry is mostly just dead weight.

Of course if your goal is to have a little fun with your cutlery and your food load is light because you donít plan to stay long or hike far, then by all means indulge (assuming you are not in violation of local regulations). I do the same and I do it a lot. In fact, the true ultralight packer would scoff at my 35 lb pack but pack weight ultimately is determined by what you plan to do in the wilds. If you want to meditate, indulge your senses, and put miles under your feet, you won't need books and binoculars. However, I tend to dawdle and camp more than hike. Thus my goals are a usually a bit different than the typical ultralight thruhiker. I still carry my field guides, binoculars, and a hand lens and often spend hours keying out plants, watching birds, or practicing primitive survival skills like cordage making or creating fire by friction.

If you plan to cover 100 miles in 7 days on trails that seem to climb more than they descend, you may want to think twice about how badly you need to satisfy that tremendous urge to chop. If you have little experience backpacking, the reality is that your knife needs will usually be far less than you probably imagine. You may want to think small. And instead of carrying one large knife or tool, you might also consider carrying several smaller ones. This has the advantage of redundancy. If you lose one or break a blade, you will still have a backup.

|

| A sharp pair of scissors can be handy for a variety of tasks in the backcountry. The Manager II (1.1 oz) can fill that niche and provide a pen for leaving notes, sharing addresses or marking your bird checklist. Itís a nice complement to the Camper or Pioneer. At 1.2 oz for the Okapi and 1.0 oz for the Opinel, these folders are worth considering as additions to the pack. Their thin blades are excellent for slicing cheese and salami, yet they are strong enough for much tougher tasks. You can also lighten your load by replacing guy and clothes lines with Kelty Triptease Lightline. Strong stuff that gleams in the night when your flashlight beam passes over it, making it easy to find your tent or tarp in the dark. The SpectraR 900 core gives it a breaking strength of 188 lbs, with a weight of 1 oz per 50 ft. |

If you carry cheese, beef stick, prepare vegetables, or clean fish, you will need to have a blade sufficiently long. If you cut stakes or poles for a tarp like I do, you will need something large enough to handle saplings of one inch diameter or so. Iíve found that the large blade on a medium size Swiss Army Knife (2 1/2 inches) is more than adequate for all of the above, although I do like to use the Swiss Army Knife saw for cutting saplings. Rather than carry one large Swiss Army Knife, I prefer to carry a medium-sized model. I find it easier to clean and more comfortable to use for precision cutting. They also make great whittlers for passing the time in camp. The Victorinox Camper (2.7 oz) and Pioneer (3.0 oz) are excellent choices and the small blade on the Camper is perfect for many whittling projects. The Victorinox Rambler (1.1 oz) or Manager II (1.1 oz) is a good complement to a larger Victorinox. In addition to small scissors which can be very useful for removing an in-grown toenail or cutting a circle out of moleskin to surround a blister, the small pen blade can be handy for digging splinters, lancing blisters, or other medical needs. The small screwdrivers can be used to repair flashlights, cameras, binoculars, spread split rings and other utility needs. Iíve used the pen on the Manager II far more often than I thought I would and recommend it as a great option.

|

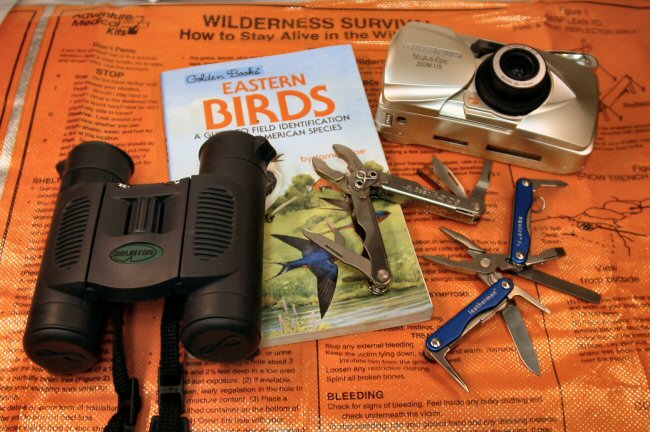

| Pliers are an essential item for repair work in the backcountry. The SOG Crossgrip (1.9 oz) and Leatherman P4 Squirt (2.0 oz) may be small in size but they are serious tools for tough jobs. Removal of a wayward fishhook is much easier if you use the wirecutters to snip off the eye first. If you like to watch birds and snap pictures of your adventures, consider downsizing your binoculars, camera, and field guide. These Brunton Eternaís have exceptional optics and are lightweight and waterproof. The Olympus Stylus is a great little camera listed as "weather proof" making it a good choice for backpacking. This one fits perfectly into an Outdoor Research Possum Pouch and carries nicely hooked to my shoulder strap for easy access. Another possibility is to go digital and there are lots of good options out there at a reasonable price for a lightweight digital camera suitable for the backcountry. |

As I mentioned earlier, I never go backpacking without pliers and my favorite way to carry pliers is nested in a small multitool like a SOG Crossgrip (1.9 oz) or the Leatherman Squirt (2.0 oz). Both of these tools have excellent pliers. Although Iíve carried the SOG for a few years and it has become a good friend, the Squirt is a solid choice because the handles are very comfortable in use, the blades are all accessible without opening the tool, and there are no cogs like on the SOG to poke holes in your pocket. Both tools have wire cutters as well as additional tools to add to your redundancy.

|

| For some, a lightweight fixed blade is considered a necessity for backpacking. These Scandanavian knives are all reasonably light and dependable. Beginning from the top and going clockwise: Helle Harding (3.7 oz), Frosts Mora Swedish Army Knife (3.1 oz), Eriksson Mora #22 (2.9 oz), Eriksson Mora 2000 (3.5 oz), and small puukko by Iisaki Jšrvenpšš (3.0 oz). A small microlight like the Photon III can save you a lot of weight. Itís attached to a Traser Glowring so itís easy to find in the dark. Bough beds are a thing of the past for backpackers so be sure to take a comfortable mattress. Although somewhat bulky, the Strata Rest is a viable option. |

Any knife you carry will cut rope and beyond that and what Iíve listed above, there isnít a tremendous number of things you will actually need a knife for while backpacking. Some people like to carry a large fixed blade in the 4-5 inch range, both for self defense and for ease of use around camp. I can certainly see the merit in that but keep in mind that ounces add up to pounds so consider your choices carefully. If you decide you want a fixed blade for camp and trail, you might consider carrying a Scandinavian model. Because many of them have partial or through-tangs, they are often much lighter than knives will full tangs of similar size. Scandinavian knives typically are made with a proven design for field use and have a long history of craftsmanship so dependability is almost never an issue. One of my favorites is an Eriksson Mora #22 in stainless, which weighs in at a diminutive 2.9 oz. In the full-tang category you might consider the Grohmann Camper, a very sturdy knife that at 3.2 oz, will not slow you down. In contrast, the Gerber Yari weighs 5.5 oz and a Dozier Professional Guides Knife weighs 6.7 oz, so be sure to weigh that fixed blade before strapping it to the pack. For an even greater contrast, consider some of the smaller "chopping" blades in the 6-7 inch class. The Becker BK7 weights in at a hefty 13.4 oz and the Busse Natural Outlaw tops out at 17.7 oz. After about 5 miles of switchbacks, that big knife will feel a whole lot heavier! And of course, you also have to add in the weight of the sheath.

A typical carry for me for a one week trip might be a Victorinox Camper, Manager, and SOG Crossgrip, with a combined total weight of 5.7 oz. A Victorinox Ranger weighs less at 4.1 oz but you still lack pliers. A Leatherman Wave gives you pliers but at a cost of 7.9 oz and you lose the tweezers, toothpick, pen, small blades, and a lot of redundancy.

|

| Another great lightweight option for backpacking is a neck knife. The Cold Steel Bird and Trout weighs in at a tiny 0.8 oz and will cut rope, clean trout, and dig splinters. The Benchmade Tether at 1.5 oz is a sturdy, comfortable blade worth considering for camp chores. In addition to light weight, neck knives have the advantage of ease of access. The Stormproof Matches from REI are the best wind and waterproof matches Iíve ever found. When the wind is relentless, you will be glad you brought them along. The Boy Scout Hot-Spark ferrocerium rod is a great lightweight back up for fire starting. |

Thus, there are quite a few choices out there for the backpacking knife lover that wants to lighten his or her load but still be well prepared for the trail. Choose carefully and you should never have a problem. But please donít be the novice with the big chopper who leaves his calling card in campsite after campsite in unsightly partially chopped trees and logs. I may not be hiking in true pioneer wilderness anymore but I still like to enjoy the illusion.

©2003 Terry M. Trier